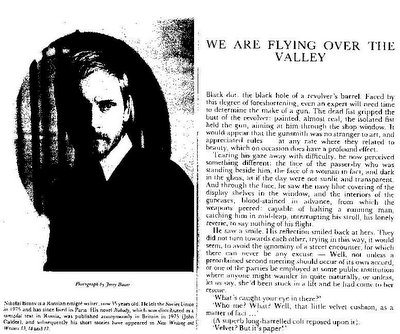

We are Flying Over the Valley

Translated by Sophie Lund

New Writing and Writers 20. John Calder, London 1983. <> ‘Kovtcheg’, Paris 1982

<> Revised by the author Paris 2005

Black dot: the black hole of a revolver’s barrel. Faced by this degree of foreshortening, even an expert will need time to determine the make of a gun. The dead feast gripped the butt of the revolver: painted, almost real, the isolated fist held the gun, aiming at him through the shop window. It would appear that the gunsmith was no stranger to art, and appreciated rules – at any rate they related to beauty, which on occasion does have a profound effect.

Tearing his gaze away with difficulty, he now perceived something different: the face of the passer-by who was standing beside him, the face of a woman in fact, and dark in the glass, as if the day were not sunlit and transparent. And through the face’s filigree, he saw the navy blue covering of the display shelves in the window, and the interiors of the gun cases, bloodstained in advance, from which the weapons peered: capable of halting a running man, catching him in mid-leap, interrupting his stroll, his lonely reverie, to say nothing of his flight.

He saw a smile. His reflection smiled back at hers. They did not turn towards each other, trying in this way, it wood seem, to avoid the ignominy of a street encounter, for which there can never be any excuse – Well, not unless a preordained second meeting should occur of its own accord, or one of the parties be employed at some public institution where anyone might wander in quite naturally, or unless, let us say, she’d been stuck in a lift and he had come to her rescue.

“What’s caught your eye in there?”

“Who me? What? Well, that little velvet cushion, as a matter of fact…”

(A superb long-barrelled colt reposed upon it).

“Velvet? But it’s paper!”

And he felt vexed, as if reality was now to contain yet another prosaic detail, but then isn’t reality made up of details anyway? If everyone of these details were suddenly – through his hastiness – to turn into paper, what would become of reality itself? How simple it would be to strike a match and to watch as the page became charred at its edges, turned itself into a suffocating little tube, destroying if not everything, then at any rate the middle, the end, and as in the present circumstances, the beginning. But, be that as it may, there is a little something to reality – there is fire, for instance, or water.

Having drunk the water, he stayed with the glass in his hand. It’s so easy to sift through the fragments of your life, without any intention, incidentally, of putting them on public view, and just occasionally to make a hitherto non existent picture emerge. There were times when he would breast the last row of hillocks, laden with grape wines and grapes, the fruit covered in dust, some with crusty sides, others which had even cracked open (how the wasps swarmed above them!), and see the deserted shore, where there was no one, no one – just a black speck over there, a dog in all probability, judging from the speed at which it moved. The strong wind of the region carried it closer to the oncoming wave, and he would follow the black speck with his eyes as it zigzagged to and fro.

Or, hardly out of the sea, he’d feel the heat under his feet, soon the sand would begin to burn – after he had taken his twenty-first step, according to calculation which dated from the time when he used to amuse himself with science. But the palm of his hand would be cold still: he’d touch the hot skin of her shoulder, brushing over the shoulder blades, and a little train of goose pimples would run like lightning down her back, rounding her thighs before disappearing, anticipating the movement of his hand, premonition and guide at one and the same time. The hand, already hot, sets off in pursuit.

Or: how is living, mortal man to avoid that day when he sees a face, absolutely still, no longer able to come close, lips which can no longer speak a single word, not even the name of one who was dear, a friend, or simply pleasing, a companion. What is this? Fear, or pity, or parting? Not yet – after all the body lies here, very close, people still sob aloud or just weep soundlessly. And when the parting does come, oh, the hope for a reunion in another existence: has my touch really had its fill of your hair, your cheeks, your shoulders, your thighs…and even your toes? And had my lips really followed the night long path of my hands, and has the honey of kisses really melted all away? But there comes a dawn with a different face: flowers at the bed head, their scent mingling with another dangerous, frightening, scent – faint no longer, already heavy, edging out the air.

And are these the components of a picture? A deserted shore, the two of them, and death which waits for the setting of the sun. if you put these fragments together – they will merge into each other – how can such a picture not be realized? All that remained would be a little in a café, in a dimly lit corner, a glass, perhaps, of beer, and the mighty neck of the proprietor: he sees me as a feature of the décor. He is Russian, he says to one of his customers. Others turn round to have a look; too late: scraps of the torn page float in the air, together with the death which has not happened.

Theirs heads nod: the mighty purple neck, the other thin necks, so that is what they are like, the Russians, well, well… that is what they are like. The scraps of torn paper sink slowly to the ground, fold themselves up: the shoreline curved like a bow, the hills, the waves. They are walking slowly along the edge of the sea, and if the shore does not come to an end, if there is time to add to it – working feverishly, oblivious to any word let alone gesture – they will go on walking, chatting to each other, or just with their hands touching, and he will see the living seaweed of her eyes, and never the cold reflection of clinical light, and the uninterested pupils. It’s too much! Too much! screeches the head on the mighty neck: waiters mop up the customer, the glass of a beer mug crunches underfoot. Naturally, the won’t let me extend the shoreline on paper.

But they are carefree now, those two, stepping lightly on the sandy shore.

A lunge forward: I could be in time, I could… Too much! Hello! How’s things! screeches the parrot, a feature of the décor. The scraps of paper fall one after the other, together with the parrot, the customers, with death: although not at once, they glide through the air. The sweet, cold, night air.

The day before: a layer of lipstick on her mouth. She came to close to the mirror: in the mist suddenly obscuring her face, she could have seen only a small scarlet ring, a circle, almost a dot, almost an oblong scar. The man – curly headed… just a moment, I can’t quite see… that’s better… curly headed, dark, sluggish – did not get from the bed. He felt a burning sensation on his chest, coming from the surface of his skin, as if from a sting. “It burns”, he said. “What?” “It burns.” “Where?” she turned away from the mirror in such a way as to cause her unbuttoned blouse to fly up around her shoulders and appear quite black in the half light of the closed shutters. The burning sensation was below his left nipple, and she thought that she saw something there… but then calmed down. “It’s all normal.” I think that it was exactly on this spot that yesterday, leaning over him, (she was trying to reach the cheese), she has dropped hot ash from her cigarette. “It burns? Well, that’s strange, isn’t it. Never mind, it’ll go away.” She kissed the place, and saw the imprint: almost a circle, just like a ring. It was because of the extra greasy layer of lipstick on her mouth that a trace appeared on his chest, just under his left nipple, or rather a little below the fifth rib, counting from the bottom. He put his clothes reluctantly, listening with irritation to the sports news, and for some reason, to the rest of the news as well: petrol prices had jumped, and as for coffee, the least said the better. The Russians, as usual, wanted a lasting peace… the experts insisted that this was so… and in any case were still far away.

“We’re off to see the gang”, he said. She took a last look in the mirror – a fleeting, rapid, glance.

The car would not start for a long time. (Well, this isn’t true: they get into the car, the door almost slams on her dress, but no, it’s all right. The engine starts immediately).

Elements we know well: fire, air, water, earth. In their pure form they are rarely present when death and love occur, which are themselves also elements, but, without our participation, of no interest to anyone save perhaps philosophers. Life presents of itself a mixture of elements in equal proportions, but should one prevail over the others, something great is born. For instance, a conflagration is fire prevailing. An ocean: water. Two figures stand high on a hill – a man and a woman, most likely in an embrace – high on that hill air holds dominion since, after all, in motion it becomes wind and causes the sleeves of the young woman’s blouse to fill and billow. Obviously, there is earth too, underfoot – at any rate under their feet – but we are not concerned with it.

Observe well proportioned life: an appetizing dish bubbles on the Prometheus’ fire, strong hands wash a thick neck under a jet of water. A fan turns. Love and death conform: a woman, full of energy, gazes despairingly at her husband’s back, and at the same time glances with impatience at the telephone. A cat enters with a mouse in its teeth – probably it’s a toy mouse made of rubber. Of course there can be no death here: these people are immortal.

There is one element which has not been mentioned, and this is unjust: it muddles all the others, changes them in places, its name is madness. It does not know love, hides it, forces you to see an instrument of death in a kiss, and transforms each gesture into danger. It is a powerful element, I tell myself as I walk down the stony path from the top of the hill: the deserted shore, the absence of any human being and, from the deserted sea, the road which stretches at the base of the pine trees, between the hillocks, towards the deserted little town. Steep cobbled streets, dusty café windows, a half opened door, and looking as if it has been newly washed, the window of the gun shop. The collar of an unbuttoned blouse is reflected in the glass. “Do you like it?” “Who me?” “Look at that beautiful dagger – it comes from Spain.” The knife rested upon the velvet paper, a little apart, not very broad, but with an ornate handle and a distinctly visible narrow groove on the thick side of the blade. Childhood friends used to tell me that the groove was there to drain the blood. And for a long time I believed this explanation, until they laughed at me, those friends of my youth. It’s the hard rib, they told me, which stops the knife from bending even when it meets bone, and enables it to do its work.

The half opened door of the café: the sound of a song wafting through. “Do you know that song? No? Why not, I rather like it”. He listens to the words. “We’re flying over the valley, where we were born, where we walked beside the stream, and loved, and died… not so fast, don’t fly over it so fast.”

“You have a strange accent. Are you from the south?” Am I from the south? From the north more like.

“From the north.”

“But you were born in the south?”

Where was I born? Must I remember? Isn’t enough that one is born at all on this earth, that, somewhere, one cries out for the first time – from fear of course, at the sight of all those yellows circles in the dark shifting mass, of that sun piercing the crown of the tree beneath the window.

“Well you know, you see… I was, well I was a deaf mute. I began to speak, as it were, when I was thirty years old, and so probably…”

“But you’re much younger than thirty! I would never had thought you were thirty!”

He was already planning to develop this deaf and dumb theme.

“Incredible! I thought you were twenty – oh, say – twenty five at the most!”

Past the little hills, the vines – yellow and deserted on the red earth – along the stony, whitish road: they climb to the crest of the hill, and already only their silhouettes can be seen, as if they are climbing up to the sky, to the little cloud with a rosy rim. Navy blue wedges of evening shadow slice into the hillocks, the greenery is going darker. The sea appears, and the islands: the distant ones scarcely defined against the fog which is drowning the area. There is no sound of birds, and only gusts of wind bring the sudden sound of waves: taut white long-bows advancing towards the shore. There is just a solitary black speck moving, probably a dog bowled along by the wind – it runs in zigzag.

With every step the sea grows louder – already there is the din of rollers beating against the breakwater. Night. Fog. Moon. The sharp silent flashing of the lighthouse. The ruins of a little summer shack – in all probability the kiosk of a newspaper vendor, or some other – but wait, ice creams were sold here, and cold drinks! Of course, that’s what it was – there’s the head on the mighty neck raising itself from the deckchair, the woman, not yet devoid of all attraction, in the next chair. Summer flesh under the awnings, radios, music, fruit, and the mighty neck supporting the steady head, folds hanging down from the body like some insignia of prosperity, the armour of wealth.

He buys an ice cream, a packet of nuts – almonds to begin with – and then peanuts, a can of Coca Cola, and six cans of beer. Pausing for thought, he adds a ham sandwich, a pâté sandwich, a little carton of cold meat salad, and some chocolate. Strong fingers undo the purse, take out a hundred frank note (bearing the portrait of Corneille), but then discover something smaller: fifty francs (with Voltaire: oh, philosopher of Ferney, can your wisdom really be exactly twice as cheap as literature?) The wife feigns sleep, hiding her face beneath a magazine: the cover shows Russians marching. She sees standing beside her a pair of hairy calves, her gaze travels upwards along the pale blue veins which stand out in abundance on the thighs, (that is the nature of the job, all your life on your feet, you understand, behind the counter), her gaze travels higher still to the pendulous belly: she pretends to be asleep. Meanwhile, a mountain of emerald blue water grows on the horizon, until those who are lying down can no longer see the sky. It crashes down on the sand, washing away bodies, garbage, disintegrating the wooden walls of the stall with a cracking sound, splintering the shards of broken boards, and in receding carries away a shoal of white sandwiches.

The ruins are covered in sand. Night. Fog. Moon. Lips whisper a name. The hot palm of a hand touches cheeks, hair: the face is paler than the surrounding night. He sees the lids twitch, suddenly laying bare the eyes: she would see the moon, or rather a pale blotch in the fog; she sees his face.

Night. Buildings line the railway tracks, but they leave room enough for waste land: waste land. A man’s silhouette beside the motor car, the little flame of a cigarette. Wires hang down like staves: you can just hear music. If you strain your ears, there is a rhythmical crunch of gravel beneath the feet of an approaching man, even several men, perhaps there are three of them with but a single thought. The lone figure beside the motor car feels the tension of waiting, detaches itself from the car, becoming barely visible; the black patch has moved away from the pale patch of the motor car, and dissolved. They halted in a semi circle a short distance away, but the crunch of the gravel did not cease: skirting them from the side, a fourth man was coming towards him, a stranger, and yet here was something about the contour of the head that reminded him of someone he knew, and was waiting to meet that night.

He felt as if he had been stung on the breast, a sudden burning sensation, which having begun on the surface, was now penetrating deep inside. Last night, leaning against his stomach to sip wine out of a glass, she had spilled hot cigarette ash: music, warmth, alcohol. The music of an old record, with the hum of a needle, the ash breaking off, falling, falling, burning: the place marked, and the burning sensation growing more and more acute with every step of the man who was coming towards him. The burn, starting at one point on his skin, and then penetrating deep was the reason why he didn’t feel it: the blow, as if something had snagged his ribs, bent the bone, and entered. There was only something hot, running down over his belly under his clothes, down into the groin and lower still, spilling over his naked legs, his feet which became numb immediately, and his toes – gathering between them, soaking the leather of his shoes, and the gravel, and the earth beneath them.

Arms flung wide, a man motionless. The torn strap of a raincoat. The lamp aims its pools of light, the giant button shines.

It is too late to tear up the used page.

“I want to tell you something… but you mustn’t laugh, all right?”

What exactly, he wondered. The seaside café was deserted. The proprietor stood behind the counter, wiry, with swift eyes which saw everything at once: a blouse, seemingly violet in colour, showed beneath the woman’s jacket. A man in a peaked car drew up in a rickety motor car and carried in a bundle: the newspapers.

What, exactly, does she want to tell me? Does she – he sipped his coffee, feeling the warmth flow downwards inside his body. Probably – it’s not to be excluded – she’ll tell me that she is married, and how sorry that makes her. That she is only going to be here for another day or two – three at the most. Four perhaps. No, it’s unlikely to be four, two days at the very outside.

”But look, you aren’t going to laugh are you?”

With what speed I gain this sort of reputation! – he said to himself. Everywhere and always, not without foundation of course, but it’s getting to be too much. she leaned towards him, holding back the hair which cascaded down all the same, hiding her face, and he could just catch: “I am happy… I am well.” He parted her hair, and met her gaze: it held an explanation, the reason why, and he could already read, as if he were deaf, those same words on the scarce moving lips. Her pink cheeks were lit by the sun: warmth spilled through the air, and the sun threw its rays further and higher: the shelves which held hundreds of bottles flared like a collar of northern lights, green and dark blue and ruby red, blood red – the colour of blood predominated on the shelves. The proprietor’s face was yellow in the sunlight. He screwed up his eyes, a grimace of displeasure froze on his face for the remainder of the day.

Does he see that the man with the young woman is agitated, (is he happy or the reverse?) His forehead, cheeks, nose have reddened: he uncurls the palm of her hand, and lays it against his face: the sent of waterside willow, bitter bark, damp grass – where does it come from? He breathes in the freshness of the cool palm, and the sounds of his native tongue fill his hearing, he even says something, and only then realizes that he is speaking an abracadabra to her, the language spoken there, in a far away corner of the earth where people have quite other pursuits, distinctly other – to be precise, they study the science of death and madness, where morning and evening gravel crunches beneath the feet; where it is always: Night. Moon. Wasteland.

Her hair covers his face: “With you I am so, I don’t know, do you understand…”

The jacket slipped from her shoulders and he could see them portrayed in the mist of the sun drenched blouse. He saw the face in the mist, and the white chairs on the terrace, beaded with dew. He pulled himself together, asked the proprietor for a newspaper, and unfolded it with deliberate slowness. Morning. In bold type: The Russian in Africa, and a photograph with a caption which said: ‘Russians Marching’. In smaller type: squaring of accounts. In the vicinity of Debussy Parade… identity not established… lipstick… according to police opinion, drug traffickers…

The page of the newspaper bent back to itself. She was smoking another cigarette, gazing absent-mindedly at the photograph of the murdered man. And then he saw interest, and attentiveness, and a look of pain suddenly gripping her face. She got up and rushed to the counter: “L’horaire de bus, please!” She said ‘horror’ instead of ‘timetable’. But they are accustomed to accents here.

Hello! It’s too much! how’s things! screeches the parrot, and at the same time whistles a little in surprise. This, of course, is not all the proprietor says – nearly, but not all. The parrot is in clover: the proprietor has gone to the bank, while his comely, still attractive wife is on the telephone, smiling an uncertain smile, as if listening to something agreeable, and as if she can be seen by her interlocutor. She is talking, without any doubt, to a man – playing with the salt cellar, the pepper and mustard pots which she has taken from their stand: forming a triangle out of these powerful seasoning, pepper, mustard, salt. Absentmindedly, she pushes the untidy mustard pot to the side – so far to the side that it almost falls behind the counter. Pepper and salt are left: the well-groomed little fingers move them around, as if performing some strange dance, foretelling something, and then suddenly squeeze the neck of the pepper pot: the knuckles grow white. It’s too much! How’s things! screeches the parrot: the proprietor is away, he’s at the bank, there are few customers. The parrot’s conversational gifts are unrivalled.

But to this vaguely grubby café in the capital, I prefer the one in the far provinces: descending from the hill along the stony road, past the houses shut up until summer, past the trees which step further and further back from the sea. A grey day, wind, rain. Pieces of wood on the shore, washed white – heavy, naked – resemble the bones of some dinosaur. In front, a dog runs in zigzag, bowled along by the wind, its paw prints are already blurred at the edges, half erased.

Good morning, we say almost in unison, the proprietor and I. Hastily, he produces a cup of coffee: he is reading a fresh copy of Morning. I open the page. Her face, which yesterday morning was beside me, and the evening before, and the night, is now a different face: it shows sorrow, silence, peace, as if it belonged to a runner who has stopped running, and has had time to catch his breath. ‘Last night … made an appearance … aware of the identity … on Diu(misprint)bessy Parade … 19 years of age, member of an engineer’s family…’

A penetrating gaze: the wiry proprietor studies the face of yesterday customer, gathering himself, holding himself taut and at the ready, meeting the customer’s eye: beads of sweat break out above the thick eyebrows, as if dispensed from a dropper beneath the skin, the words freeze upon lips which have turned blue: You were here yesterday, and so was she…

He could say no: to the end, everywhere and at all times he would deny, as he practised it from infancy. Would he deny the lips whispering his name, the heavy beat of the waves in the distance, and the earth shuddering beneath the assault of the water.

‘Yes.’ Along the road to the top of the hill, covered in crooked trees and bushes bearing berries the colour of dried blood.

Going out, he can already hear the whirr of the telephone dial, and begins to run through the sea shore scrub, his choice of route totally devoid of logic: he’ll slip in the rain. Here and there, his wet clothing is wreathed in steam, he is gasping for breath. A car catches up with him on the rise to the highway: How to get to … – I’ll go with you, it’s on my way to Toulon, I’ll show you.

He sees a face in the rear-view mirror: plastered hair, panting mouth, can that be him? It is, also.

A double row of slightly murky walls, with a narrow passage between them, half-filled by a broad back. Her face is far away, at a distance of two or three paces, and her voice is unrecognisable: a distorted telephone voice masked by a fine wire mesh. She kisses him – he sees the lips part a little, the lids close. He watches, pushing with his hands against the glass which nothing, not even a heavy calibre bullet, will puncture. ‘My darling,’ he hears, ‘my darling, kiss me, come closer, touch me…’ He kisses her, as if the transparent wall, with its black spot, a squashed dead fly, does not exist, and he hears: ‘I don’t know why, how nor what… tell me: didn’t we stay together…’

‘Look: black cliffs, and the sea beneath them, and the waves which lose their strength and their shape upon the shore. The music of the reeds, bending like waves beneath the wind which fills your blouse – I see a triangle of sunburn skin, smooth and shiny. Little snakes of sand slither round our feet, the faded sun sinks lower, clouds stand in a semi-circle, echoing the line of the shore. Further away, the dark green hills are etched against the dark blue sky, and the silhouettes of those walking along the stony white road merge when they reached the highest point, and even if you were to hurry after them, you would not reach them in time: night advances upon the hills, covering them in shadow, and only the moon lights the path – white, running with chalk, like a belt thrown in the thick grass, like arms flung wide.

The moon shines through the window: a gold earring glitters on the table, elongated like a drop of water flying trough space, and the glitter of the gold is repeated by the shimmering skin, and the paths left by the moist palm which rounds a thigh, trembling, and the rapid pulsation of his blood in his swelling veins, and the breath which burns his face as if the air were on fire: as if their breathing filled the room, the hills and the valley…’

‘My darling’, he hears. He cannot make out the face, hidden by the oval of misted glass, but he sees, rising from the depth, an expression almost of pain.

‘Get it over!’, the policeman says, bending towards his ear, but it’s no use: the surge of manhood leaves him.

‘Your visit is over.’

Two white patches: her hands, pressed to the transparent wall opposite, separated from his wall by the corridor. The broad back tears their gaze apart, the well cut uniform, the layers of muscle, but he manages to hear: my darling…

‘ Allow me to express the hope that your influence will prove beneficial,’ someone in nicely tailored civilian clothes tells him.

A sunny day. Absentmindedly, he buys a newspaper, unfolds it. The black patch of a headline: DEBUSSY. But no, it’s nothing, nothing, some concert or other, it’ll pass, it happens and then it passes, the main thing is to shut your eyes and not see, not hear, sit it out, nothing, nothing.

It’s completely unimportant who – who, by the way? – is guilty, whether it is she or others, but in fact he forgot to tell her so, has only just thought of it: I will always be on your side, together with the hills, the valley, the road, the moon, together with warmth which comes from some unknown corner on the earth, with that drop of gold – he opens the palm of his hand: as if caught in flight, an elongated form pierces his skin with its sharp end: the gold earring, dulled by blood.

He notices another reader of newspaper leaning almost right up against the kiosk opposite the entrance to the railway station. A light coloured belted raincoat. The feeling forgotten since he left his motherland, rises slowly within him. His muscles fill with strength. Walking lightly, he embarks on the circle of the approaching chase.

A far corner of the station lavatory. And the reader of newspaper, damn it, suddenly feels the need, but stops, goes no further. He, meanwhile, takes cover behind the little structure of the urinal, as if intending to go in, but then chooses another course of action: after all the decorative concrete fence is only a little taller than he is himself.

Street. Evening. He is alone.

The parrot’s cage is covered by a black cloth: it’s time, my friend, you’ve talked enough all this long day, for you night has come, as it has for us too: the time of the late drink, of unrealized meetings, of indolent imaginings. The mighty neck above the cash register: the proprietor is vague, gazing out like a Buddha. Further away, at the little tables, conversations are drawing to a close. The cold cigar clamped between the teeth of the customer standing in a some picturesque pose at the counter. The lamb, frozen in its niche below the arch of the sign which says ‘ Restaurant’, eyes glittering as if alive, but alas quite lifeless, stuffed, or worse still, a waxwork. Upon the mirror, the length and breadth of the entire wall, blooms an enormous bouquet, blooms one year, two, three, and longer: the painted artificial flowers have faded.

For a moment the street sounds grow louder: probably the door has opened, probably someone has come in. A woman’s voice requests a glass of lemonade. Silence. The woman voice requests again a glass of lemonade. The popping of a cork. The rattle of change. The click of the juke box, set in motion. The steel claw moves along the row of black discs. Slowly the needle begins its approach… nearer and nearer to the edge of the shining black disc, nearer and nearer – I find I am even shaking, I am even… Among the artificial flowers I see a dark head.

“We are flying over the valley… we are flying over the valley… we are flying …”

<< Home